Gross Anatomy: In This Political Climate, When Are We Right to Feel Disgusted?

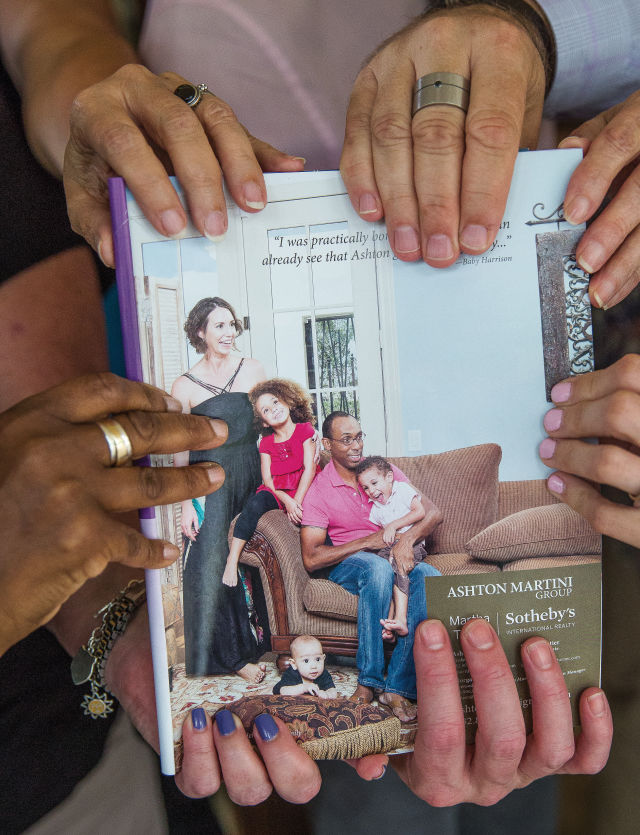

A couple of years back, Ashton Martini, who sells houses for Martha Turner Sotheby’s International Realty, decided to create a series of print advertisements to publicize his services. “I wanted them to be something cool and different,” he said, “not just a picture of a house and me.”

Eventually, he hit on the idea of ads featuring actual families to whom he had sold houses. “Most of my clients become my friends anyway, so it seemed like a fun thing to do.”

The first family Martini chose, which also turned out to be his last, was a young couple with three children who had recently bought a home of his in River Oaks. The ad was shot in the family’s new living room, with the father seated on a sofa holding one of the children, his wife standing nearby, and the couple’s toddler staring adorably at the camera from atop a pillow on the floor. It pleased Martini immensely. On the downside, it was expensive to produce, and “was such a pain in the ass between the makeup and photographer and the stylist,” he decided to abandon his idea for a series.

The ad ran in several local publications in early 2015 without incident. Later that year, however, just days after its appearance in an issue of Houstonia, Martini noticed an email on his phone while driving. The subject was “Disgusting Ad,” and the brief accompanying note, from a doctor in Tomball, read: “Your ad in the June Houstonia Magazine is DISGUSTING! I will not put this magazine in my reception area!”

The ad that started it all, in our June 2015 issue.

Image: Stuart Mullenburg

The doctor offered no further explanation for his disgust, although he did include his phone number and an offer to discuss the matter further. “I thought maybe it was because the baby was on the ground or the mother wasn’t wearing shoes or something,” Martini recalled. Puzzled, he called the man, who picked up right away.

“What do you have to say for yourself?” said the doctor. “It’s disgusting.”

“I don’t understand,” Martini answered. “What’s wrong with my ad?”

“You’re promoting interracial relationships, and I will not have that in my office.”

Martini, who’d been driving on 27th Street in the Heights, had to pull over and stop the car. “I was shaking,” he remembered. “I was not prepared for that to be the issue.” He explained to the doctor that the couple in the ad—a white woman and her black husband—were friends as well as clients.

“I don’t care who they are,” came the reply. “You’re promoting interracial relationships.” The doctor continued by saying that either Martini or the family—Martini wasn’t sure which—should be “eliminated,” and although much of the rest of the conversation is now a blur, Martini does remember calling the doctor a racist and a bigot. He also remembers trying to reach out to him.

“I said, ‘I’d love to sit down and talk to you about this because I don’t understand where this is coming from.’ And he said he would never sit down with anyone like me.”

At the time of the incident, I was the editor-in-chief of Houstonia, and when word of Martini’s altercation with the doctor reached my desk, my jaw literally dropped open. I found it unbelievable that anyone could still espouse such an opinion. I felt angry, yes, but also nauseated, sick to my stomach, repulsed by the idea that a physician, of all people, could be so hateful.

In short, the man’s words disgusted me. After talking with my colleagues, who’d had a similar reaction, we decided to take the unusual step of canceling the doctor’s subscription. Then, after the magazine received a phone call from a second reader objecting to the ad—the man told us that he’d taken the issue straight from his mailbox to the trash because “I just don’t go in for racial mixing”—I wrote an editor’s note to Houstonia’s readers telling them about the response the ad had received, and how we’d decided to respond to its detractors.

Published online as “Racist Readers Need Not Apply,” the note provoked an immediate, enormous reaction. Within 24 hours, it had reached tens of thousands of people around the country via social media.

In the days that followed, the magazine received hundreds of messages of support and gratitude for taking a stand against the doctor’s bigotry. Someone in suburban Chicago wrote that she’d given me a standing ovation in her living room. A woman on the east coast said that my note “transcends regional bounds and speaks to humanity’s truths.” A journalist in St. Louis wanted to move to town to work for Houstonia. The chief of the San Antonio Fire Department gave me a citation for bravery. A woman in east Houston offered to bring coconut shrimp fried rice to the entire office. KHOU covered the controversy on the 10 p.m. news, my actions were lauded by writers from Salon to the Dallas Morning News, and I was invited to write a story on my experience for the Washington Post.

The near-universal praise I received was utterly surprising and utterly gratifying, especially for the editor of a young magazine trying to build an audience. It also felt like a personal vindication of sorts, given the public’s generally dim view of journalists these days. And however impulsive my decision had been to cancel the doctor’s subscription, thousands of people had agreed that I’d done the right thing.

But why was it right for me to trust my disgust, I wondered, and wrong for the doctor to trust his? When is disgusted the right thing to be?

For as long as humans have walked the earth, disgust has taught us to wince, recoil, revolt and flee. Rarely, however, have so many been so disgusted at the same time, it seems, or by such a variety of stimuli. We have lived through a season in which one man’s disgust for Mexicans, Muslims, a Latina beauty queen, breast milk, sweating and bathroom breaks was embraced by millions, and also a season in which one man’s disgusting attitudes toward women led millions more to embrace his rival. Of late, Americans have claimed to be disgusted by everything from terrorism to Olympic swimmers, police shootings to ATM fees to—of course—presidential politics. Disgust is, to put it mildly, having a moment.

Increasingly studied by brain scientists, debated by philosophers, championed and scorned by pundits of every stripe, disgust nonetheless remains an emotional mystery. Beyond its physical manifestations—the feelings of queasiness, the wrinkled nose, the eew reaction and instinct to turn away—no consensus has emerged about what disgust is, what forces induce it, or what role it plays, or should play, in shaping our moral views. When it comes to disgust, it seems, the only thing everyone agrees on is its power.

That, and we all hate lice.

Lice Clinics of Texas now operates three facilities in the state.

Not far from its western terminus some 20 miles from downtown, Memorial Drive narrows into a rivulet of small office parks and strip malls dedicated to miscellany. A tuxedo rental store, a Napoli’s pizzeria, a donut shop and nail salon may be found in one of these, all coexisting peaceably with Jessica Evans’s and Michelle Sunshine’s shop, a business born of a scream.

“My first-grader had been scratching her head,” Sunshine told me, recalling her days of denial a few years back. The Austinite suspected dry skin for about a week, until a close inspection of her daughter’s hair revealed the real culprit. “I saw bugs—running—around,” she said, the memory still producing a yuck face years later. She isn’t sorry she screamed, especially given what came afterward, although Sunshine does regret jumping several feet away from her daughter. “I was that mom that just flips out.”

“We met through lice,” laughed Evans, who by then was already running a small business doing home treatments for the bugs. Sunshine, like most parents, had turned to traditional lice-killing methods, which involve applying an oily insecticide solution, followed by laborious combing to remove the insects’ eggs, or nits. After a few years of battling them with her daughters—“they were like the lice-mongers,” Sunshine laughed—she was at wit’s end. “It was combing and combing for hours, and crying, and all this stuff, and the oil. It took up your life for two weeks. It killed me. I just couldn’t take it.”

Why do we find lice so disgusting? “Because they are bugs in your hair, and that’s gross,” replied Sunshine confidently. “The only place they live is the human head, which is creepy.” Adult pediculus humanis capitis, which are the size of sesame seeds, use their six claws to climb from strand to strand of hair, feeding on blood several times daily, with females laying around four eggs a day. And while head lice are often wrongly associated with unsanitary habits (“lice actually like clean hair,” said Evans), and no longer transmit diseases like typhus, we still associate them with dirtiness and fears of contamination, both of which are integrally connected to the disgust response, as we’ll see.

In desperation, Sunshine called Evans, who’d had great success with a relatively new lice treatment method involving a box-shaped comb that blows heated air into the hair, instantly killing the insects and dehydrating their eggs. During the 90 minutes it took for Evans to perform the heating and combing procedure on one of Sunshine’s children, the women discovered they were basically the same person: both were constitutionally peppy Austin moms whose two children had struggled with lice, both were unfazed by the stigma, and both owned pugs. “It was meant to be,” said Sunshine.

So in 2014 the duo opened a treatment facility in their hometown, later expanding to Houston last March and San Antonio in October under the Lice Clinics of America brand, although the atmosphere is anything but clinical. As of now, only the Austin outpost serves wine (“lice are very stressful,” Sunshine reminded me), but all are bright and cheerful, offering few clues to their actual purpose.

And because a technician does the actual killing and combing of bugs, patrons never even have to see them. Eliminating the gross-out factor has meant brisk business for Sunshine and Evans, as has the recent emergence of a strain of super lice resistant to insecticides. On average, each clinic treats 100 to 150 cases of lice a month, at $185 a head, which is to say that the pair’s venture is decently profitable, if not disgustingly so.

“They’re really smart,” said Tamler Sommers. He was talking about octopuses. “They’re as smart as dolphins practically, but nobody gives a shit about them because of how weird they look.”

“Exactly,” David Pizarro replied. “Meanwhile, the wombat, or whatever those cute animals are that are essentially rodents—”

“—who an octopus could run circles around intellectually,” said Sommers.

“You should have a campaign to dress up octopuses in cute outfits,” Pizarro laughed, “and therefore prevent them from being killed and eaten.”

The above exchange is from an early episode of the Very Bad Wizards podcast, in which, per the subtitle, “a philosopher and a psychologist ponder the nature of human morality.” It is the brainchild of Sommers, an associate professor of philosophy at the University of Houston, as well as a highly listenable combination of braininess and BS such as only two bright men with an equal affection for rude humor and the is-ought problem could produce. Since 2012, they have held court on everything from slavery reparations to tattletales, examining hot-button topics through their respective prisms. New installments appear every few weeks, and these days the podcast gets around 15,000 downloads per episode (sample titles: “The Repugnance of Repugnance,” “Lies, Damned Lies, and Ashley Madison”).

As it happens, Pizarro is something of an expert on disgust, having conducted a number of studies on the emotion at Cornell University, where he teaches psychology. His findings have demonstrated strong relationships between disgust and everything from anti-gay attitudes to political conservatism to colonoscopy avoidance. As such, disgust is a not infrequent topic on the podcast, with both men trying to unravel the mystery of its origins and power.

“For the most part, everybody agrees that disgust evolved in humans originally as a means of avoiding contamination, and as a means of not eating really bad food that could make you sick,” Sommers told me. “Rotting animal carcasses, things like that. And so we developed this aversion to things that might be contagious, and might also make us ill, so that they don’t look appealing to us at all.” Hence the disgust provoked by vomit, feces, germs and the like. But those aren’t its only triggers.

By the time a now-infamous video containing Donald Trump’s lewd and disturbing remarks about women was first broadcast to the world, on October 7, GOP insider Jacob Monty had already felt revolted by the Republican nominee for more than a month. Monty’s conversion might be dated to 8:31 p.m. on August 31, when Trump took to the stage to “have some fun” at a rally in Phoenix, at which point Monty still considered himself an enthusiastic supporter.

Having met privately with the candidate at Trump Tower less than two weeks earlier, Monty had concluded, along with the other dozen Hispanic leaders present, that the Republican presidential nominee represented the best hope for immigration reform in America, Monty’s signature issue. The El Paso native and longtime Houston lawyer had helped arrange fundraisers for Trump, made the case for him in an op-ed piece for the Chronicle, and defended his positions on cable TV.

Around 9:05, however, something came over him, a feeling he later found difficult to describe. It wasn’t anger, he recalled, and in any case, Monty wasn’t the sort of man to let anger get the best of him. Still, it was an emotion just that deep, powerful and propulsive—within hours he would publicly denounce Trump and resign from the candidate’s National Hispanic Advisory Council. Last September, well before the lurid revelations still to come, I asked him if the conservative blog RedState had perhaps put its finger on the feeling in an article published the day after Trump’s Phoenix rally: “Hispanic Surrogates for Trump Walk Away in Disgust After Last Night’s Rhetoric-Heavy Speech.”

Yes, he said. Not unlike 55 percent of the rest of America—if a recent Pew Research Center poll is to be believed—the presidential campaign had left him disgusted.

As Trump proceeded that evening with what he termed a “detailed policy address” on immigration, Monty sat and watched the speech on TV with his wife. And by the time the candidate reached the fifth point in his 10-point plan, Monty had heard enough.

Point five, you may recall, promised to cancel President Obama’s executive orders temporarily protecting undocumented immigrants. To Monty, Trump was calling for “the immediate repeal of the executive action that protects the DREAM Act kids”—the million or so immigrants who were brought to this country illegally as children. That would have “put the Dreamers, which are the best of the community, up for deportation. These are kids that didn’t decide to break any rule. They just followed their parents over here. And they have clean records.”

The hardline, “everyone must go back” stance and angry tone shocked the immigration lawyer, not least because he had heard neither during the meeting at Trump Tower. The candidate had been “humble” and “engaged,” he remembered, frequently jotting notes during the 90 minutes he spent with the council. During one memorable moment, according to Monty, “he said, ‘look, I understand people aren’t excited about deporting these people that are not criminals…. I’m not excited either. I don’t want to do that.’”

Every exchange he had with the Republican nominee that day left Monty more and more certain that Trump had no intention of deporting 11 million illegal immigrants. Indeed, he seemed to believe that doing so would be not only impractical but wrong. Trump seemed eager to read the immigration proposal the council had written, and while “he never committed to one way of solving the issue,” Monty recalled, “it was very clear that he was not in favor of deporting the 11 million.”

There are many possible explanations for Monty’s prodigal 34-minute journey from fan to foe: Trump’s obsession with “criminal aliens,” his apparent capitulation to the demands of Ann Coulter, Alabama Senator Jeff Sessions, and other immigration opponents. (“My conclusion at the end was that he really listens to whomever speaks to him last or speaks to him the loudest.”)

But what finally moved Monty to action was disgust—disgust with the candidate, disgust with himself and fellow committee members for allowing themselves to be used as “props,” disgust with a man he thought he knew.

How is it that behaviors we consider immoral—and the people who engage in them—come to disgust us? The theory, said Sommers, is that “we have all these emotions that help to enforce norms, rules, and values, emotions that are there to motivate us to behave morally, to punish people who don’t behave morally.”

Immoral behavior by others can make us angry, for instance, while our own immorality can induce shame and guilt. Indeed, some emotions seem crucial to the creation and reinforcement of moral judgments. But how did disgust become one of these? A popular view, and one which Sommers is not completely persuaded by, is that “this thing that we already have for a completely different function was coopted by this process…as a way to motivate us to act and cooperate with other people and coordinate with other people.”

Over time, the argument goes, we evolved into creatures capable of being disgusted not just by urine and raw sewage and dirty diapers but other human beings, and “not because we think they’re contagious—we’re not trying to eat them or anything—but because of what they do or something about their character.”

Whatever the origin of the connection, our emotions are far from reliable indicators of good and bad. We prefer wombats to octopuses not because wombats possess an inherent goodness, but because we’re hard-wired to be more empathic toward animals that resemble us. “The more something looks like a cute baby, the more we like them,” as Sommers put it on the podcast.

Disgust can be similarly problematic. The sight of an amputee or someone who is morbidly obese can trigger feelings of disgust in some, even though neither poses a threat. Similarly, we can be disgusted by things that are good for us, like eating crickets, which are quite nutritious. Thus, the question of when we should trust our decisions to disgust, if ever, is a crucial one for Sommers. “Is this something we should listen to? Is this something that should inform our moral judgments?” wondered the philosopher. “Or is it something that we should be on guard against and really never trust?”

Pizarro the scientist is consumed by a similar question. When it comes to emotions like disgust, he asked on the podcast, “how do we figure out when they’re being good signals and when they aren’t?”

These are not only academic concerns. From time immemorial, provoking disgust has proved an effective means of galvanizing public support for moral crusades, and not a few immoral ones, sometimes with deadly consequences. The Very Bad Wizards have repeatedly examined—and laughed at the ludicrousness of—an infamous 2010 YouTube clip known as “Eat Da Poo Poo,” in which a pastor and leader of the so-called National Task Force Against Homosexuality in Uganda purported to reveal the results of his own “research into what homosexuals do in the privacy of their bedrooms.”

In front of a shocked and revolted audience, Sommer explained, the pastor announced that “the thing that gay people do is eat poo poo out of people’s behinds. It’s a way of saying that these people are sick, they’re depraved, and you cannot allow them to contaminate our society.”

Fear of contamination can be an especially powerful driver of human behavior, one which demagogues have long manipulated “to exploit or oppress or exclude whole classes of people,” he noted. Which leads us back to Uganda. After new and stricter anti-gay legislation was enacted in 2014, the country has seen a sharp increase in homophobic violence.

“Do you personally dislike homosexuals?” a CNN reporter asked the country’s president after he signed the bill into law. He replied without a moment’s hesitation.

“Of course. They are disgusting.”

In October 2015, just a month before the Houston Equal Rights Ordinance was put before voters, a majority supported the measure. Its stated intent had been to protect 15 groups—pregnant women and the disabled among them—from discrimination in matters of housing, employment and the like, and it was a misinformation campaign about one of those groups, the transgender population, that ultimately doomed it. The erosion of HERO’s public support is usually traced to the Campaign for Houston PAC, which branded the ordinance a “bathroom bill,” instilling fear in voters that under the law, men could not be barred from entering women’s locker rooms, showers and, crucially, public restrooms. A TV ad depicting a menacing figure stalking a young girl in just such a facility was particularly effective at recasting the bill as a threat to the safety of the city’s children.

But fear was not the only emotion appealed to by the anti-HERO camp. In courting a public largely unfamiliar with the needs and lifestyles of transgender persons, the campaign made little effort to distinguish biological males utilizing women’s restrooms because their gender identity is female, and those doing so to prey on little girls. In one radio ad, a woman identified only as Rashinique imagined undressing at the gym while a man stood next to her. “That is dangerous,” she said. “That is filthy. Honey, that is creepy.”

In other ads, a pair of community leaders, longtime HISD principal Herlinda Garcia and Rev. Kendall Baker, called the ordinance “sickening,” although their efforts paled by comparison to the Campaign for Houston’s first spot in August 2015, featuring an unnamed young woman who cheerfully hoped one day “to be pregnant, and deliver my beautiful baby right here in Houston.” The tone of the minute-long ad shifted abruptly, however, when she spoke of men having access to women’s restrooms. “That is filthy, that is disgusting, and that is unsafe,” said the woman, who claimed to oppose the ordinance “on behalf of all moms, sisters and daughters.”

“Sorry, sister. You don’t speak for me,” wrote Lisa Falkenberg at the time. “I don’t find solidarity in your ignorance.” To the Chronicle columnist, the Campaign for Houston’s tactics were a clear indicator that the group was less interested in protecting children from predators than finding a “a way to defeat an ordinance that partially benefits a group of people whose lifestyle they don’t support.” And inasmuch as mobilizing social conservatives was crucial to that effort, it was no accident that the anti-HERO forces targeted the bathroom, Falkenberg claimed. After all, “the more grossed out you are by public restrooms, the more conservative you are likely to be,” she wrote, citing the work of moral psychologist Jonathan Haidt, which indeed found a correlation between disgust sensitivity and conservative views.

More to the point, other research has noted that people can be made to discriminate against minority groups if disgust has been aroused in them, as David Pizarro showed in a fascinating 2011 study. Participants were given a questionnaire asking about their views regarding various social groups. Each filled it out in the same lab at Cornell, but some did so after Pizarro and his team had sprayed the room with what the study termed a “disgusting odorant.”

“It was a fart spray, which you can get at any novelty store,” Pizarro told me. “An assistant sprayed it in the garbage can in the corner.” For the most part, the researchers found that participants’ attitudes toward, say, ethnic groups and the elderly were not swayed by the smell in the room. There was one important exception, however. Study participants who filled out questionnaires in a smelly room reported negative attitudes toward gay men much more often than those who hadn’t. The researchers’ findings, however surprising, seemed to confirm the powerful effect that disgust can have on moral judgments, an effect it appears to share with other emotions. “If you elicit fear,” said Pizarro, “you get greater negative judgments about black men…. The two different emotions play off the different types of stereotypes and threats.”

In a poll conducted by the Kinder Institute last spring, 73 percent of Houston residents said they believed it was “very important” for the city to pass an equal rights ordinance, a seemingly paradoxical finding, given that HERO had been rejected two-to-one by voters just a few months earlier. In survey after survey, however, Bayou City residents consistently cite the city’s diversity of cultures and lifestyles as among its greatest strengths. All of which begs the question: Was fear-and-disgust-driven manipulation all it took to persuade Houstonians to vote against their consciences?

For his part, Tamler Sommers believes that a public unaware of transgender lifestyles was crucial to the anti-HERO camp’s success. “I don’t know that many people were that familiar with them,” he said, counting himself among the unfamiliar camp. “I mean, it’s not that I hadn’t heard of people who had undergone sexual transformation, but I didn’t really know anybody.”

Our tendency to be disgusted by people and groups we are unfamiliar with—particularly when their foods, hygiene and sexual practices differ from our own—has been documented by several studies, and may have an evolutionary basis.

“Because disgust is so closely linked to contamination and disease, there would be good reason to be wary of members of a group that you haven’t had contact with,” said Pizarro. “They could very well be carrying diseases that you’ve never been exposed to.” In the present case, he added, “there is something extra that’s working against the transgender community”—numbers. The fact that “there are so few of them—in terms of percentage of the population—reduces the opportunities for others to humanize them.”

His view suggests that transgender discrimination by the larger population will only continue unless such opportunities increase, unless both groups somehow come together. For while familiarity might breed contempt, unfamiliarity breeds disgust, and dangers of its own.

Last May, I received an email from Caty Borum Chattoo and Leena Jayaswal, two filmmakers based in Washington, DC who’d heard about Houstonia’s run-in with the doctor. The women, both mothers raising children in biracial families, told me they were working on a documentary about the challenges still faced by families like theirs today, 50 years after the landmark Supreme Court decision legalizing interracial marriage. (Their film, Mixed, is scheduled to be released in 2017.) After I forwarded some of the many letters of support I’d received from Houstonians, the women asked if they could come to town and interview me, as well as some of the letter-writers, none of whom I’d ever actually met.

So it was that six of the latter showed up at the magazine’s offices in July, along with Chattoo, Jayaswal, and their camera crew. The readers’ enthusiasm for my actions, I discovered, hadn’t dimmed in the many months since they’d first heard about it, and for the next three hours, we had a candid discussion about race relations in Houston.

At the Houstonia offices last July, a documentary crew films a discussion on race in the city.

There was Kayla Dar, a blonde, white woman from Magnolia married to a Pakistani man. In replying to my editor’s note, she’d written that she didn’t “even know where to start on our racist encounters and how badly it hurts our children.” Dar wore an exhausted expression as she recalled the many times her kids had been called “mutts,” and she and her husband “mixed breeders.”

Monée Fly, a red-headed woman “so white I tend to glow in the dark,” but who is “actually 35 percent Native American,” let out a gasp. “I really thought that as a society…we were bigger than that,” she told the group. “That we had grown up.”

Pat Menville, whose father was Mexican, vividly remembered getting beat up in fifth-grade for using a whites-only water fountain. She was both shocked and personally offended by the doctor’s reaction.

“How dare somebody be like that in my backyard,” Menville said, telling the group that while not a native of the city, Houston was the only place that hadn’t made her feel like an outsider. “That’s what made me so angry. This is my home.” She wondered why “we keep putting up these fake cardboard dividers” of race, ethnicity and the like. “Why does that make us happy?” If “you’re stuck in traffic in Houston, you’re stuck in traffic in Houston,” she said. “There is no race.”

Across from her was Karen Celesta, the group’s sole African-American member, who’d been angry too, writing that people like the doctor were “nasty, horrific monsters and must be battled if America is to survive.” But she was also mystified by them, she told the group. “If you confront people with this mindset, and I have,” she said, “they can’t even tell you why they feel that way. It’s ‘I don’t know,’ ‘I’m not sure,’ ‘it’s just wrong,’ or ‘I just hate it.’ Well, why?”

“Ignorance and education are not mutually exclusive,” sighed David Byrne of The Woodlands, who couldn’t get past the fact that it was a physician who’d espoused such opinions. “Good Lord,” he imagined telling him. “You’re educated, you’re a medical person. You know everybody is the same underneath.”

Fly nodded. “I find Dr. Tomball ‘DISGUSTING’!” she had written. “I would hope a man of scientific medicine would practice a little more open-mindedness, maturity and restraint.”

Trisha Keel chimed in. “There are no pure races and we don’t want pure races,” said the former HISD teacher. “That’d be like having a bowl of soup that had only celery in it.” Keel, who attended the high school formerly known as Robert E. Lee in the ’60s, wished the doctor had looked beyond skin color to see a loving family in the ad. “If you put love back into the equation,” she said, “there is none of this.”

Karen Celesta shook her head. “That’s something that’s ingrained in him,” she said. “You can’t fix him.” A far better strategy, she offered, would be to build a world of racial equality around the doctor, backing him into a corner, into “that hole that he’s in. Let him stay there and stew in it.”

“I just want to change his mind,” said Fly.

That sounded like a dangerous idea to Keel. “He will just sit there and fester. You don’t need to try and fix him. What you resist persists.”

There were a few more moments of disagreement that afternoon, but mostly I felt moved by the discussion, moved that such a diverse group of people could be so united in indignation at the doctor’s actions, so united in longing for an end to America’s racial nightmare. But his absence from the discussion grew more conspicuous as the day wore on. For a group that prided itself on inclusiveness to exclude the doctor seemed more than a little hypocritical.

In truth, I’d wanted to invite him. In fact, I’d made several attempts to reach the doctor, ever since his opinion first reached my desk. He communicated with me just once, however, last summer, after I’d requested an interview with him for this article. “In my experience,” wrote the doctor in an email, “journalists have an agenda that they want to promote, and any published rendition that results from an ‘interview’ is not in any form or fashion representative of what the person being interviewed had actually said or attempted to say. Consequently, I decline your invitation.”

“Well, what did you expect?” Sommers said when I told him of the response. “You’d trashed him in a magazine.” Rather than cancel the doctor’s subscription, cut off contact, and denounce him to “an audience that completely agrees with you,” I should have engaged him, he thought. “Too often now, we get into our protective bubbles. People who disagree with us, we don’t ever talk to them.”

In short, when given the opportunity to humanize the doctor I’d refused it, just as the anti-HERO forces had refused their chance with the transgender community. “But the way people’s minds get changed is by having more contact with people on the other side, not less,” Sommers said.

It was certainly true that no one’s mind had been changed, that no real good had come of my actions. But then, disgust never claimed to be a force for good. Its only real purpose, now and always, has been to help humans quickly identify threats—be they lice or lifestyles, pathogens or politicians—and then avoid them by any means necessary. Disgust advises against everything and advocates for nothing. It separates and divides, locates hidden perils, builds walls. It frowns on intimacy, cooperation, the joining of hands—anything that might risk contamination. And in making dangerous that which poses no dangers, it frequently becomes dangerous itself.

But there’s something else about disgust, too, something it shares with our other emotions: It can be overcome. Whatever their sensitivities, doctors somehow get over the sight of blood, parents learn to take dirty diapers in stride, kids don’t turn up their noses at brussels sprouts forever.

And so, with that in mind, I’ve restarted the doctor’s subscription to Houstonia. Who knows, maybe his disgust with the magazine—and the changing city it chronicles and celebrates—will evaporate with repeated exposure.